A Brief History of Doomscrolling

News fatigue is nothing new

When Charles Dickens first set foot in America in January 1842, he looked forward to seeing a young democracy in action—a land of engaged citizens, earnest debate, and civic idealism. It was, he imagined, a model republic.

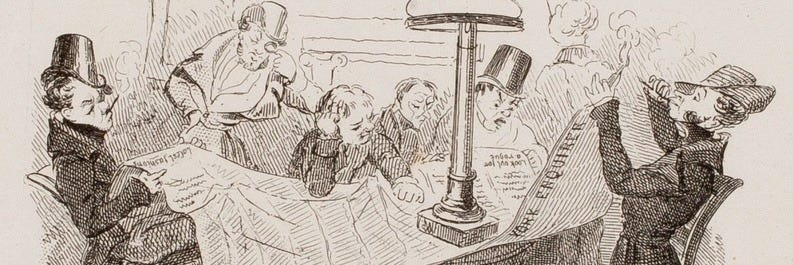

Instead, what he found came as something of a shock: a nation whose heads were buried in their newspapers.

Dickens, a former journalist himself, was taken aback by the country’s obsession with the news. He soon grew appalled at what he saw, condemning the American press as “a monster of depravity,” guilty of “pimping and pandering for all degrees of vicious taste, and gorging with coined lies the most voracious maw.”

But what unsettled him most wasn’t the press’s appetite for scandal, or even the loose copyright laws (which allowed them to republish his novels without compensation). It was the sheer volume of it all—the relentless torrent of cheap print, and the sense that a society awash in news was losing its capacity for deeper reflection.

The dynamic Dickens observed never really went away; it simply migrated to our smartphones. In 2020, journalist Karen Ho popularized the term doomscrolling to describe the early-pandemic habit of compulsive news-reading. Since then, the word has escaped its original context. Today it applies just as readily to cat videos, real-estate listings, explainer clips, and all the digital debris drifting across our screens. The content matters less than the compulsion. The doom is in the scrolling.

Doomscrolling may seem like a uniquely digital-age affliction, but its roots stretch back to the industrial information explosion of the nineteenth century. Long before smartphones and K-Pop demon hunters, our newspaper-clutching forebears were struggling with the problem of too much media and too little time.

As Henry David Thoreau observed in Walden (1854): “Hardly a man takes a half-hour’s nap after dinner, but when he wakes he holds up his head and asks, ‘What’s the news?’ … After a night’s sleep the news has become as indispensable as the breakfast.”

Complaints about information overload were nothing new, even then. Plato famously worried that writing would cripple human memory; and seventeenth-century English clergyman Thomas Fuller lamented that “so much is printed, that little is read.” But the problem took on a new scale in the nineteenth century, when an unprecedented volume of printed material began to swamp the public sphere: newspapers, cheap books, serialized fiction, broadsides, pamphlets, political tracts, religious literature, magazines, almanacs, and an ever-growing pile of bureaucratic paperwork.

To characterize nineteenth-century readers as facing “information overload” is, of course, a retrospective argument. Victorians would never have used that term; and yes, these anxieties were mostly confined to the world of literate white people. But nonetheless, plenty of readers and writers of the era reported feeling bewildered, overwhelmed, and deeply worried about what they were missing. In other words: a pervasive sense of doom, minus the scrolling.

The nineteenth-century information explosion emerged from a tangle of social, cultural, and technological changes. Industrial innovations like steam presses, Linotypes, and cheap wood-pulp paper played their part, but the real transformation occurred at a deeper, systemic level: a rapidly urbanizing United States knitting itself together into an increasingly networked, interconnected public sphere.

By 1900, the U.S. was producing half the world’s newspapers—despite holding only five percent of the global population. And the age of mass media had only begun.

The View from Nowhere

Paradoxically, the cacophony of mid-nineteenth-century media set the stage for a long period of consolidation and corporate retrenchment. By the 1880s, industrial-scale publishers like Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst were stitching together sprawling new media empires—the Meta and Alphabets of the day.

Out of this consolidation emerged a new journalistic ideal—one that would supplant the chaotic caterwaul of the mid-century press and come to define the twentieth century: the sober, neutral, just-the-facts mode of reporting sometimes called “the view from nowhere.”

Through much of the twentieth century, a relatively small number of gatekeepers—media conglomerates, wire services, broadcast networks, and syndication outfits—filtered the world’s events into a nightly broadcast or a morning front page. What it all lacked in personality it made up for—more or less—in precision, consistency, and a broadly shared perspective on what was happening in the world, what historian James Carey has called the “iron core” of midcentury journalism.

Then the Internet shattered that consensus.

We all know what happened next. The age of mass media gave way to a hyper-networked, bottom-up era of blogs, message boards, podcasts, influencer feeds, micro-publications, hyper-partisan outlets, and algorithmic streams. The brute-force economics of the penny press—cheap, fast, sensationalist content, turbo-charged by advertising revenue—came roaring back on a global scale.

To be clear: This is not to say we are living through the nineteenth century all over again. The scale and reach of today’s global network dwarfs anything that came before. But the mass psychology of the moment feels eerily familiar: a frenetic, fragmented media ecosystem where many of us feel inundated with too much information delivered in too little time.

It’s a well-worn pattern by now: media systems scale faster than their audiences can adapt; people feel overwhelmed, even as they consume more content than ever; critics fret about a supposed existential threat to society; reformers dream up new systems to restore epistemic order; and then the cycle starts all over again.

After the Flood

Doomscrolling, seen in this light, is nothing new. Nor is it a moral failure. It’s an adaptation to a kind of built environment. And the problem has been with us for a very long time. Just as the Victorians built publishing empires and other institutional gatekeepers to manage the flood of paper, we are building algorithmic interventions to manage the digital deluge.

Today, we can see a new sort of gatekeeper emerging: Large language models (and their corporate proprietors) are trying to aggregate, synthesize, and repurpose the world’s intellectual output. Like the Hearsts and Pulitzers of old, they ingest vast quantities of data to deliver a compressed, seemingly coherent version of events. Whether they succeed or not (and the jury is very much out), they represent the latest chapter in a centuries-long story: our struggle to build systems that help us make sense of the world when our senses are overwhelmed with too much data.

Let’s be careful of stretching the parallel too far. Large language models are not editors in any human sense. They operate by statistical patterning, not by human judgment. Yet for many users, they effectively play a similar role: as a kind of gatekeeping mechanism for compressing an overwhelming volume of information into something that feels coherent and consumable.

Will today’s AI powerhouses become the digital equivalent of the Gilded Age media baronies? Will they produce the first drafts of a new kind of history? Time will tell. Our systems grow more complex, but the underlying challenge remains the same: How can we leverage new tools to harness our collective knowledge stores, without losing our innately human capacity for reflection and making meaning?

Doomscrolling isn’t a failure of human willpower; it’s a coping mechanism, and the predictable outcome of information systems optimized for speed, volume, and monetization. On the Boston docks, Dickens foresaw the problem that would come to dominate the modern world.

What ties that period to our own is not the news per se, and certainly not the technology—but the recurring tension between the growth of media systems and the cognitive limits of our human sense-making capacity. Each era seems to see new solutions emerge to bridge that gap, which in turn create new problems and new opportunities. As (the admittedly over-quoted) Marshall McLuhan put it, “We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us.”

The question is not whether we can build systems powerful enough to harness the flood—we already have. The real question is whether those systems can help us build a more coherent understanding of reality, or accelerate its fragmentation. The future of our media ecosystem—and our ability to make sense of the world around us—depends on what we do next.

Interesting article Alex. I am learning a lot